I am a big fan of the old watch factory/brand videos (such as those linked here). One of my favorite is Hamilton's "How a Mechanical Watch Works", and this particular scene caught my eye.

![Image]()

While I know vintage watches tend to be smaller before the modern big watch trend, I never realized just how small they did get. I wasn't aware of any "arms-race" to make the smallest watch movement, as opposed to the race of making the thinnest movement. Part of it is (I think) probably because in a tiny movement the accuracy is limited by physics, and in spite of all the modern advances, watch brands still thrive for new (and expensive) ways to make a mechanical watch more accurate.

Anyway, after some digging, I found out that the tiny Hamilton ladies' watch was probably powered by the 911 movement. Due to sheer curiosity, and also as a personal challenge, I bought a cheap "as-is" one from eBay with the intention of dis/reassembling it.

![Image]()

Speedy for scale.

![Image]()

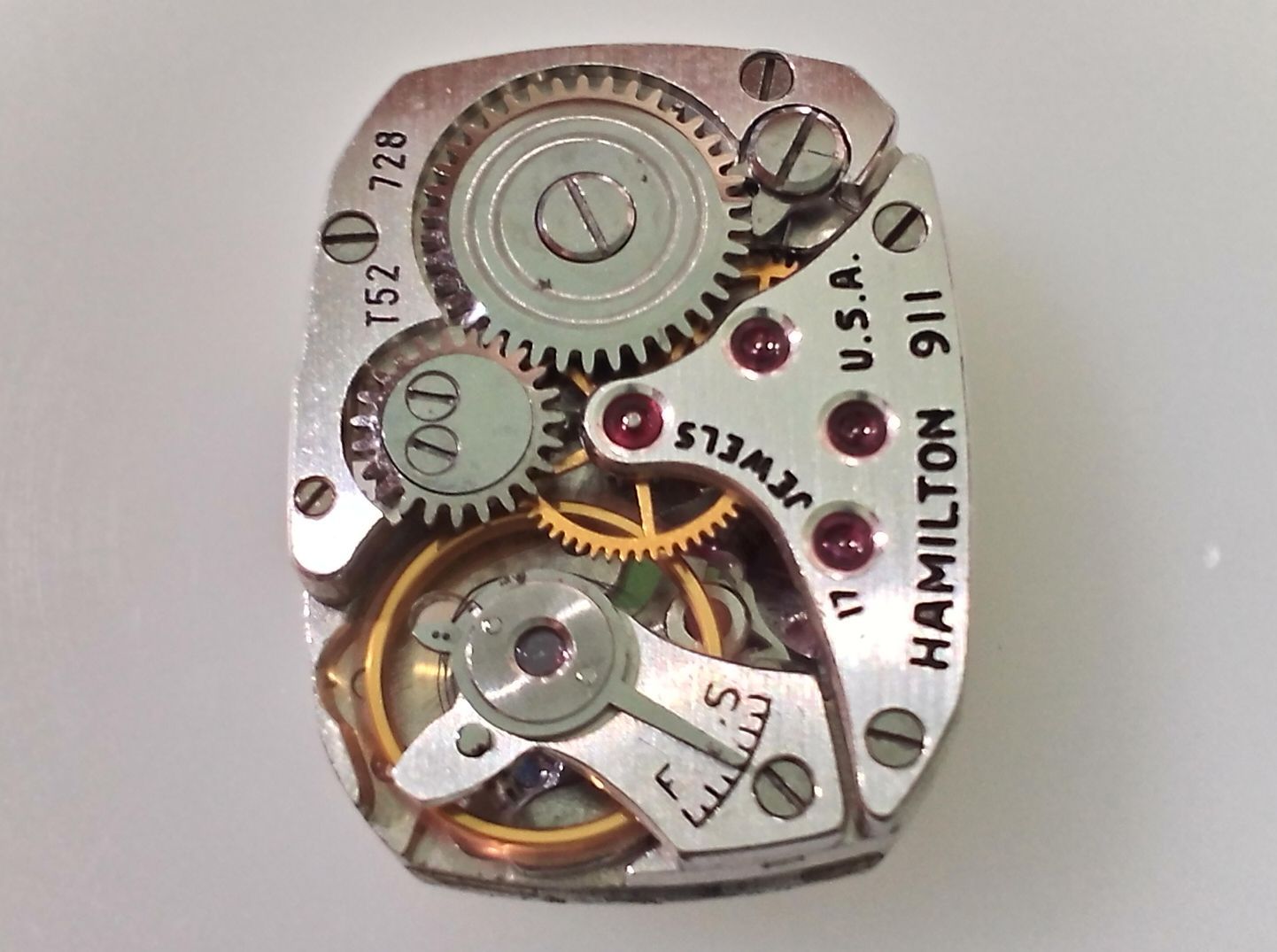

Close up.

![Image]()

I did worry about how a tiny, tiny watch is cased since I'm not sure if I have the tools to take the movement out without damaging it. Turns out the casing arrangement is... best described as a "lunch-box", which I'm sure has a fancier jewelers'/watchmakers' name for it. As you can imagine this design has no water resistance whatsoever.

![Image]()

"kreisler USA" was stamped on every link of the underside of the bracelet.

![Image]()

Apparently this is a 14k gold-filled case. A very grimy one at that. I did my best of what I can with the ultrasonic cleaner and pegwood.

![Image]()

![Image]()

At 12.1 x 15.5mm, this movement is actually smaller than those ubiquitous Chinese quartz movements. (This is a spare movement I bought for parts, which I ended up not using.)

![Image]()

Dial side of the movement. Notice the water damage.

![Image]()

Serial number T52728. Estimated production year 1939. If that's true, this particular watch is older than my parents! (Because of the aforementioned videos, I thought this was a 50s thing.)

![Image]()

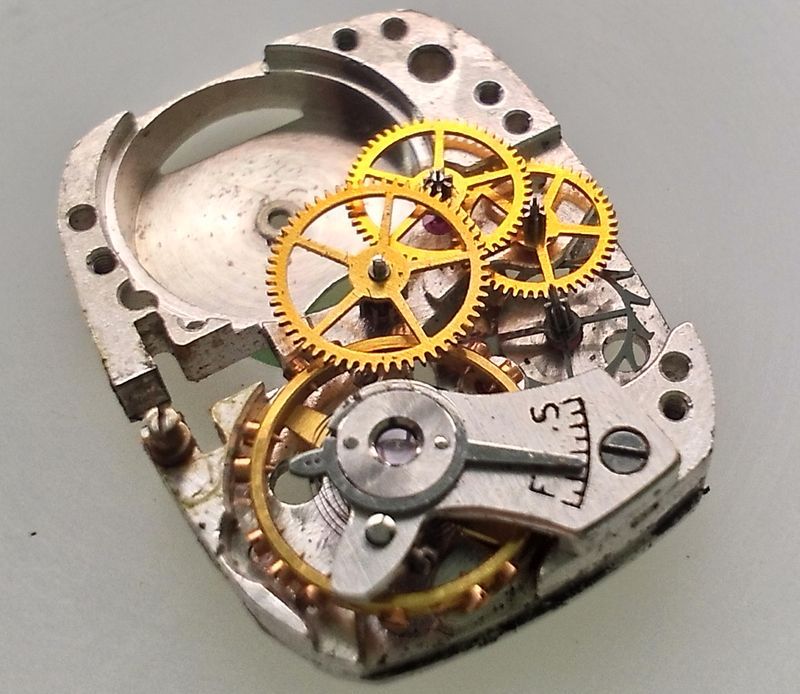

Four wheels, one plate. Reassembling this was not fun.

![Image]()

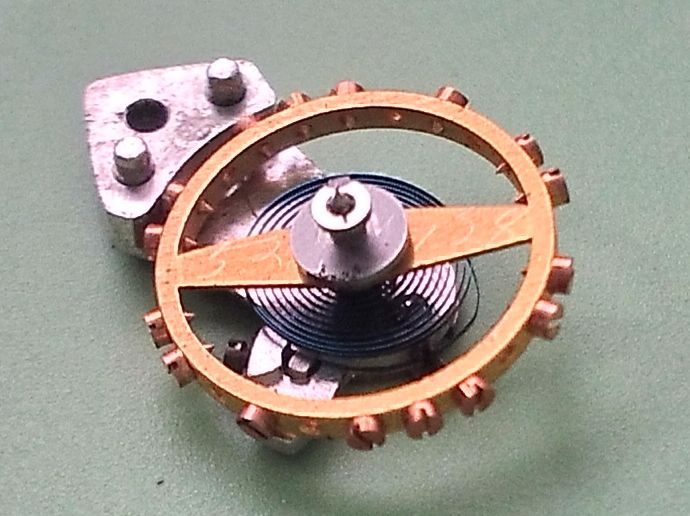

Like the Waltham, someone managed to write the serial number on the 6mm balance wheel. Unlike the Waltham, the serial number actually matches the one on the movement.

![Image]()

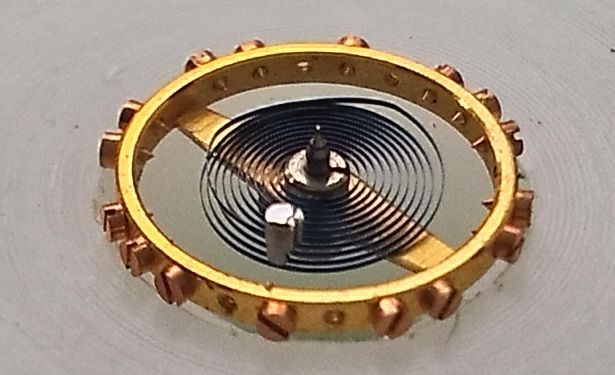

Imagine my surprise when I saw that the hairspring is actually overcoiled. On a microscopic scale!

![Image]()

Balance assembly, disassembled. The 2 screws that held the cap jewel is literally the size of a grain of sand. A minor miracle happened when I dropped one of these screw on the floor, and somehow managed to find it afterwards.

![Image]()

The screw, as shown on another excellent Hamilton video.

![Image]()

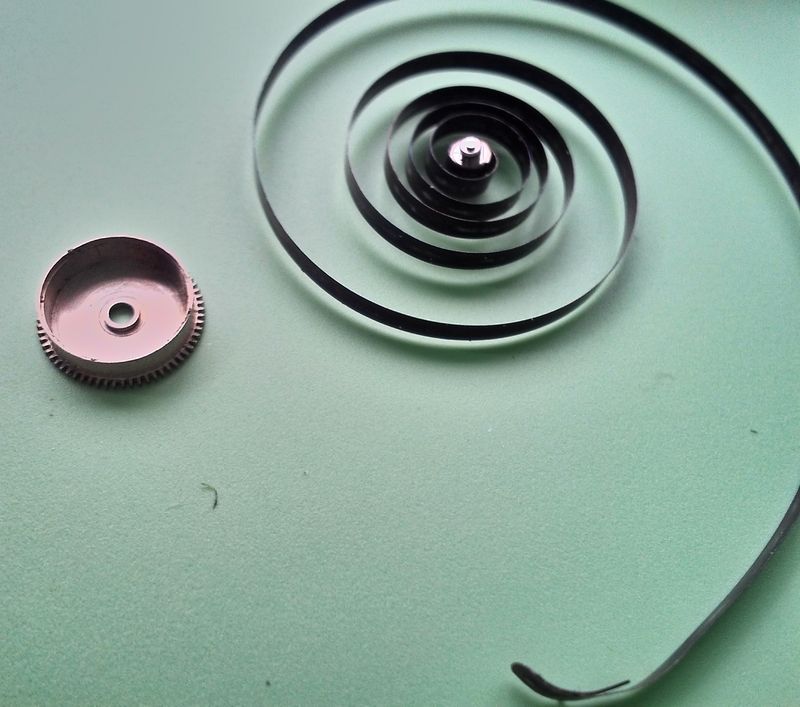

The mainspring is surprisingly clean. Assembling this is another circle of hell, and renewed my hatred of T-End mainspring.

![Image]()

Disassembled parts. Compare this with a Soviet Chk-6 movement I worked with recently:

![Image]()

It's interesting to see what parts cannot be (excessively) miniaturized due to laws of physics.

![Image]()

![Image]()

Cleaned, assembled, lubricated and (fortunately) ticking.

![Image]()

Regulating it is a bit of a hassle since the movement is actually too small for the clamp. I have to seat it in the "lunch box" everytime I test it on the timegrapher.

![Image]()

Wearing man bracelets with your watches, you say?

(Just kidding. :-d)

Anyway, this is certainly an interesting, and literally painful experience (when cleaning the movement I have to work so close to the parts that I inhaled a significant amount of naphtha fumes, giving me symptoms not unlike a hangover). This is also the first time my #5 tweezers and 0.6mm screwdriver got any significant use. I have a whole new level of respect to the amazing skills of the people involved in its manufacturing, and quite happy to own a piece of history as shown on those videos.

While I know vintage watches tend to be smaller before the modern big watch trend, I never realized just how small they did get. I wasn't aware of any "arms-race" to make the smallest watch movement, as opposed to the race of making the thinnest movement. Part of it is (I think) probably because in a tiny movement the accuracy is limited by physics, and in spite of all the modern advances, watch brands still thrive for new (and expensive) ways to make a mechanical watch more accurate.

Anyway, after some digging, I found out that the tiny Hamilton ladies' watch was probably powered by the 911 movement. Due to sheer curiosity, and also as a personal challenge, I bought a cheap "as-is" one from eBay with the intention of dis/reassembling it.

Speedy for scale.

Close up.

I did worry about how a tiny, tiny watch is cased since I'm not sure if I have the tools to take the movement out without damaging it. Turns out the casing arrangement is... best described as a "lunch-box", which I'm sure has a fancier jewelers'/watchmakers' name for it. As you can imagine this design has no water resistance whatsoever.

"kreisler USA" was stamped on every link of the underside of the bracelet.

Apparently this is a 14k gold-filled case. A very grimy one at that. I did my best of what I can with the ultrasonic cleaner and pegwood.

At 12.1 x 15.5mm, this movement is actually smaller than those ubiquitous Chinese quartz movements. (This is a spare movement I bought for parts, which I ended up not using.)

Dial side of the movement. Notice the water damage.

Serial number T52728. Estimated production year 1939. If that's true, this particular watch is older than my parents! (Because of the aforementioned videos, I thought this was a 50s thing.)

Four wheels, one plate. Reassembling this was not fun.

Like the Waltham, someone managed to write the serial number on the 6mm balance wheel. Unlike the Waltham, the serial number actually matches the one on the movement.

Imagine my surprise when I saw that the hairspring is actually overcoiled. On a microscopic scale!

Balance assembly, disassembled. The 2 screws that held the cap jewel is literally the size of a grain of sand. A minor miracle happened when I dropped one of these screw on the floor, and somehow managed to find it afterwards.

The screw, as shown on another excellent Hamilton video.

The mainspring is surprisingly clean. Assembling this is another circle of hell, and renewed my hatred of T-End mainspring.

Disassembled parts. Compare this with a Soviet Chk-6 movement I worked with recently:

It's interesting to see what parts cannot be (excessively) miniaturized due to laws of physics.

Cleaned, assembled, lubricated and (fortunately) ticking.

Regulating it is a bit of a hassle since the movement is actually too small for the clamp. I have to seat it in the "lunch box" everytime I test it on the timegrapher.

Wearing man bracelets with your watches, you say?

(Just kidding. :-d)

Anyway, this is certainly an interesting, and literally painful experience (when cleaning the movement I have to work so close to the parts that I inhaled a significant amount of naphtha fumes, giving me symptoms not unlike a hangover). This is also the first time my #5 tweezers and 0.6mm screwdriver got any significant use. I have a whole new level of respect to the amazing skills of the people involved in its manufacturing, and quite happy to own a piece of history as shown on those videos.